Spinal cord injury levels can be confusing. If you or a loved one has a spinal cord injury the condition may be explained to you with different terminology by different types of medical specialists. These differences sometimes also make it difficult for the various medical specialists who care for spinal cord injury patients to communicate clearly among themselves about the level of injury a patient is experiencing.

Some years ago, spinal cord injuries were assessed on the Frankel scale which was originally designed at Stokes Manville in the 1930s. Today, the degree of impairment in a spinal cord injury is usually assessed according to the scale designed by the American Spinal Cord Injury Association—the ASIA scale. The ASIA scale is very complete and it gives doctors a better idea of what type of impairment an individual patient is suffering from, but it is still more than a bit confusing to both patients and medical personnel.

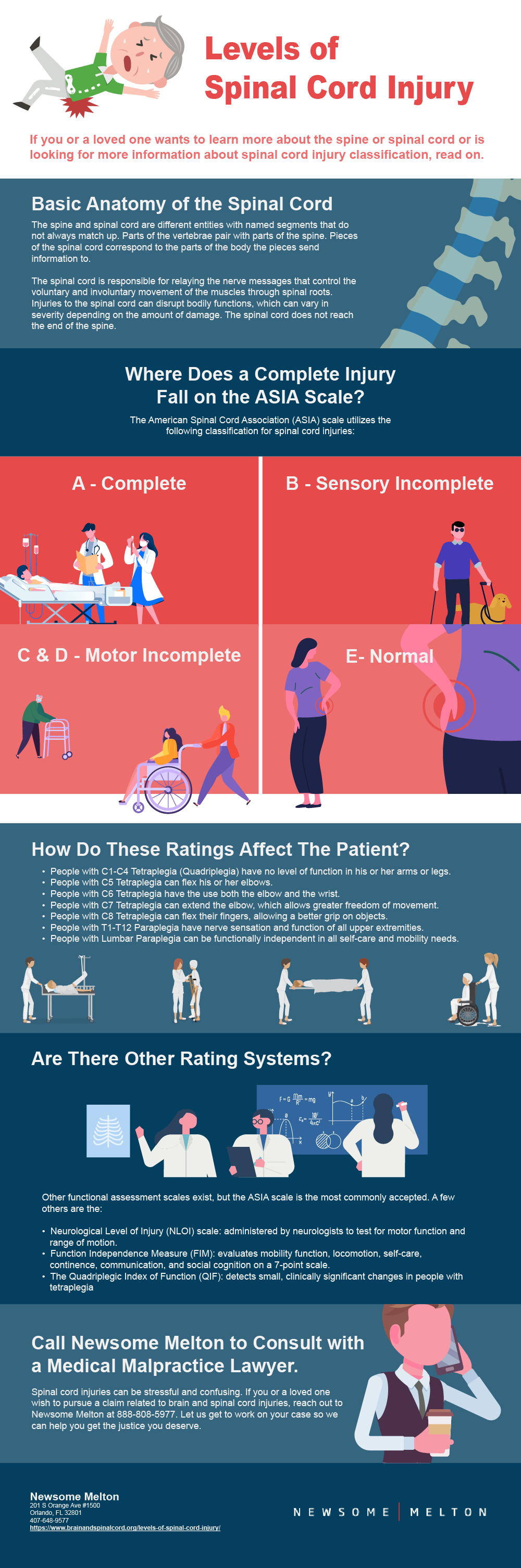

Basic Spinal Cord Anatomy

To understand this confusion and what you are actually being told when your injury is described as being at a certain level, it is necessary to understand basic spinal anatomy. The spine and the spinal cord are two different structures. The spinal cord is a long series of nerve cells and fibers running from the base of the brain to shortly above the tailbone. It is encased in the bony vertebrae of the spine, which offers it some protection.

The spinal cord relays nerve signals from the brain to all parts of the body and from all points of the body back to the brain. Part of the confusion regarding spinal cord injury levels comes from the fact that the spine and the spinal cord each are divided into named segments which do not always correspond to each other. The spine itself is divided into vertebral segments corresponding to each of the vertebrae.

The spinal cord is divided into “neurological” segmental levels, meaning that the focus is on what part of the body the nerves from each section control. The spine is divided into seven neck (cervical) vertebrae, twelve chest (thoracic) vertebra, five back (lumbar) vertebrae, and five tail (sacral) vertebrae. The segments of the spine and spinal cord are designated by letters and numbers; the letters used in the designation correspond to the location on the spine or the spinal cord. For example:

- C1 (cervical) refers to the first vertebra in the neck.

- T1 (thoracic) refers to the first vertebra in the chest area.

The spinal cord segments are named in the same fashion, but their location does not necessarily correspond to the spinal segment’s location. For example:

- The C1 vertebra and the C1 cord are at the same level, but the C7 vertebra contains the C-8 cord.

- The T1 cord and vertebra correspond, but the T12 cord is located at the T8 vertebra.

- The back (lumbar) cord is located in the chest (thoracic) vertebrae, between the T9 and T11 vertebra.

- The tail (sacral) cord is located between the last chest (thoracic) vertebra and the second back (lumbar) vertebra.

The spinal cord is responsible for relaying the nerve messages that control the voluntary and involuntary movement of the muscles, including those of the diaphragm, bowels, and bladder. It relays these messages to the rest of the body via spinal roots that branch out from the cord.

The spinal roots are nerves that go through the spine’s bone canal and come out at the vertebral segments of the spinal cord. Bodily functions can be disrupted by an injury to the spinal cord. The amount of the impairment depends on the degree of damage and the location of the injury.

The Cervical Cord

The head is held by the first and second cervical segments. The cervical cord supplies the nerves for the deltoids, biceps, triceps, wrist extensors, and hands. The phrenic nucleus (a group of cell bodies with nerve links to the diaphragm) is located in the C3 cord.

The Thoracic Cord

The thoracic vertebral segments compose the rear wall of the ribs and pulmonary cavity. In this area, the spinal roots compose the between the ribs nerves (intercostal nerves) which control the intercostal muscles.

The Lumbosacral Cord

The spinal cord does not travel the entire length of the spine. It ends at the second lumbar segment (L2). Spinal roots exit below the spinal cord’s tip (conus) in a spray; this is called the cauda equine (horse’s tail). Damage below the L2 generally does not interfere with leg movement, although it can contribute to weakness.

Sensory Levels

In addition to motor function, the spinal cord segments each innervate different sections of skin called dermatomes. This provides the sense of touch and pain. The area of a dermatome may expand or contract after a spinal cord injury.

Differences Between Levels

The differences between some of the spinal vertebral and spinal cord levels have added to the confusion in developing a standardized rating scale for spinal cord injuries. In the 1990s, the American Spinal Cord Association devised a new scale to help eliminate ambiguities in rating scales. The ASIA scale is more accurate than previous rating systems, but there are still differences in the ways various medical specialists evaluate an SCI injury.

Dr. Wise Young, founding director of Rutgers’ W. M. Keck Center for Collaborative Neuroscience explains that usually neurologists (nerve specialists) will rate the level of injury at the first spinal segment level which exhibits loss of normal function; however, rehabilitation doctors (physiatrists) usually rate the level of injury at the lowest spinal segment level which remains normal.

For example, a neurologist might say that an individual with normal sensations in the C3 spinal segment who lacks sensation at the C4 spinal segment should be classified as a sensory level C4, but a physiatrist might call it a C3 injury level. Obviously, these differences are confusing to the patient and to the patient’s family. People with a spinal cord injury simply want to know what level of disability they will have and how much function they are likely to regain. Adding to the confusion is the debate over how to define complete versus incomplete injuries.

What is a Complete Injury?

For many years, a complete spinal cord injury was thought of as meaning no conscious sensations or voluntary muscle use below the site of the injury; however, this does not take into account that partial preservation of function below the injury site is rather common. This definition of a complete injury also failed to take into account the fact that may people have lateral preservation (function on one side).

In addition, a person may later recover a degree of function, after being labeled in the first few days after the injury as having a complete injury. In 1992, the American Spinal Cord Association sought to remedy this dilemma by coming up with a simple definition of complete injury.

According to the ASIA scale, a person has a complete injury if they have no sensory or motor function in the perineal and anal region; this area corresponds to the lowest part of the sacral cord (S4-S5). A rectal examination is used to help determine the function in this area. The ASIA Scale is classified as follows:

- A – Complete. There is no sensory sensation or motor function in S4 or S5.

- B – Sensory Incomplete. There is some sensation at the level below the injury, including segments S4 and S5.

- C – Motor Incomplete. There is voluntary anal sphincter contraction, with some motor function to three levels below the motor level of the injury, but most of the key muscles are weak.

- D – Motor Incomplete. The same as C, with the exception that most of the key muscles are fairly strong.

- E – Normal. Although hyperreflexia may be present, normal sensory and motor recovery are exhibited.

What Does This Mean for the Patient?

At this point, if you are a patient with a spinal cord injury or the family member of a spinal cord injury patient you may be more confused than ever. How do these ratings apply to the daily life of someone with a spinal cord injury? A brief overview of the basic definitions may help.

C1-C4 Tetraplegia (Quadriplegia)

This is the greatest level of paralysis. Complete C1-C4 tetraplegia means that the person has no motor function of the arms or legs. He or she generally can move the neck and possibly shrug the shoulders. When the injury is at the C1-C3 level, the person will usually need to be on a ventilator for the long-term; fortunately, new techniques may be able to reduce the need for a ventilator.

A person whose injury is at the C4 level usually will not need to use the ventilator for the long-term, but will likely need ventilation in the first days after the injury. People with complete C1-C4 quadriplegia may be able to use a power wheelchair that can be controlled with the chin or the breath. They may be able to control a computer with adaptive devices in a similar fashion and some can work in this way. They can also control light switches, bed controls, televisions and so with the help of adaptive devices. They will require a caregiver’s assistance for most or all of their daily needs.

C5 Tetraplegia

People with C5 tetraplegia can flex their elbows and with the help of assistive devices to help them hold objects, they can learn to feed and groom themselves. With some help, they can dress their upper body and change positions in bed. They can use a power wheelchair equipped with hand controls and some may be able to use a manual wheelchair with grip attachments for a short distance on level ground.

People with C5 will need to rely on caregivers for transfers from bed to chair and so forth, and for assistance with bladder and bowel management, as well as with bathing and dressing the lower body. Adaptive technology can help these people be independent in many areas, including driving. People with C5 tetraplegia can drive a vehicle equipped with hand controls.

C6 Tetraplegia

People with C6 tetraplegia have the use both of the elbow and the wrist and with assistive support can grasp objects. Some people with C6 learn to transfer independently with the help of a slide board. Some can also handle bladder and bowel management with assistive devices, although this can be difficult.

People with C6 can learn to feed, groom, and bath themselves with the help of assistance devices. They can operate a manual wheelchair with grip attachments and they can drive specially adapted vehicles. Most people with C6 will need some assistance from a caregiver at times.

C7 Tetraplegia

People with C7 tetraplegia can extend the elbow, which allows them greater freedom of movement. People with C7 can live independently. They can learn to feed and bath themselves and to dress the upper body. They can move in bed by themselves and transfer by themselves. They can operate a manual wheelchair, but will need help negotiating curbs. They can drive specially-equipped vehicles. They can write, type, answer phones, and use computers; some may need assistive devices to do so, while others will not.

C8 Tetraplegia

People with C8 tetraplegia can flex their fingers, allowing them a better grip on objects. They can learn to feed, groom, dress, and bathe themselves without help. They can manage bladder and bowel care and transfer by themselves. They can use a manual wheelchair and type, write, answer the phone and use the computer. They can drive vehicles adapted with hand controls.

Thoracic Paraplegia

People with T1-T12 paraplegia have nerve sensations and functions of all their upper extremities. They can become functionally independent, feeding and grooming themselves and cooking and doing light housework. They can transfer independently and manage bladder and bowel function. They can handle a wheelchair quite well and can learn to negotiate over uneven surfaces and handle curbs. They can drive specially adaptive vehicles.

People with a T2-T9 injury may have enough torso control to be able to stand with the help of braces and a walker or crutches. People with a T10-T12 injury have better torso control than those with a T2-T9 injury, and they may be able to walk short distances with the aid of a walker or crutches.

Some can even go up and downstairs; however, walking with such an injury requires a great deal of effort and can quickly exhaust the patient. Many people with thoracic paraplegia prefer to use a wheelchair so that they will not tire so quickly.

Lumbar Paraplegia

People with sacral or lumbar paraplegia can be functionally independent in all of their self-care and mobility needs. They can learn to skillfully handle a manual wheelchair and can drive specially equipped vehicles. People with a lumbar injury can usually learn to walk for distances of 150 feet or longer, using assistive devices. Some can walk this distance without assistance devices. Most rely on a manual wheelchair when longer distances must be covered.

Other Functional Assessment Scales

There are many other functional scales besides the ASIA scale, but it is the most frequently used. Neurologists find the NLOI (the Neurological level of injury) scale helpful; it is a simple administered test of motor function and range of motion. The Function Independence Measure (FIM) evaluates function in mobility, locomotion, self-care, continence, communication, and social cognition on a 7-point scale.

The Quadriplegic Index of Function (QIF) detects small, clinically significant changes in people with tetraplegia. Other scales include the Modified Barthel Index, the Spinal Cord Independence Measure (SCIM), the Capabilities of Upper Extremity Instrument (CUE), the Walking Index for SCI (WISCI), and the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM).